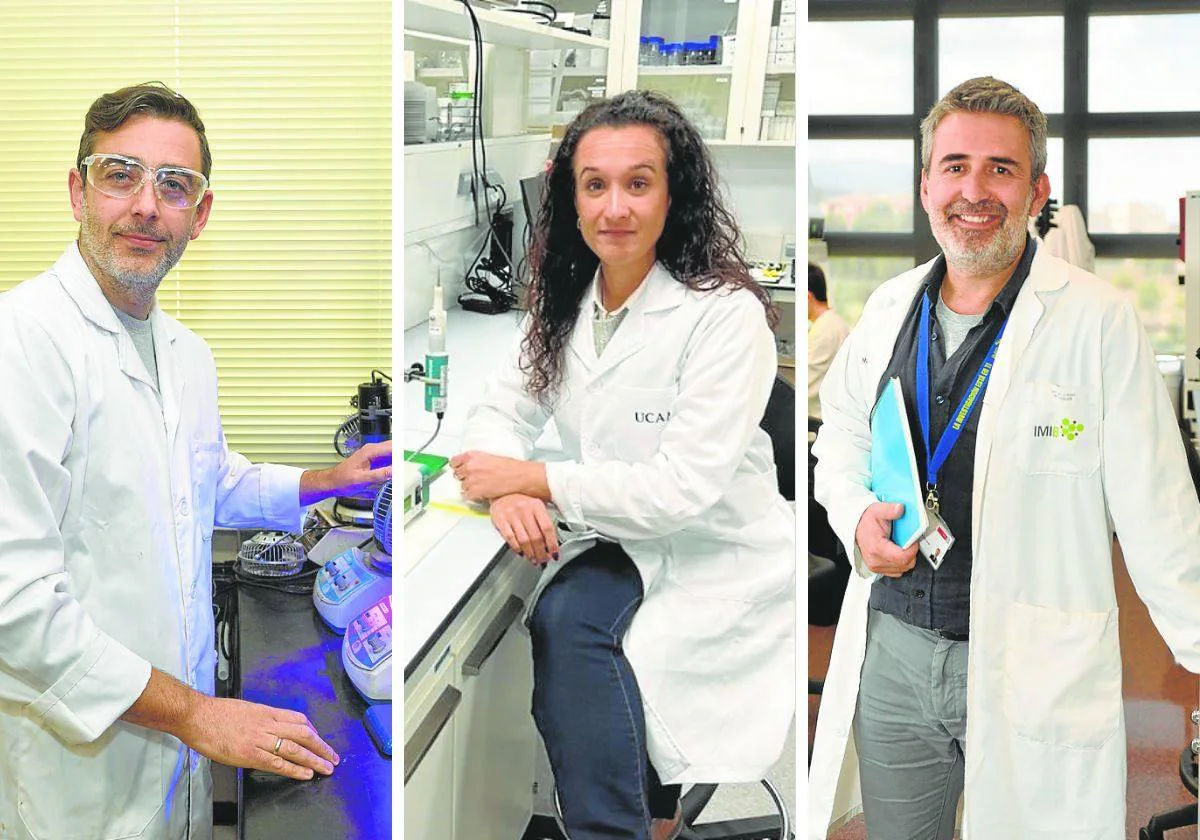

They promote high-level research in the Murcia region, protect scientific progress in the community in which they were trained, but they had to leave it to advance in their careers. They represent a message of hope for all scientists who want to return after being forced to emigrate, as they are punished by the difficulties of their research careers, financial fluctuations and job insecurity. Fabio Juliá Hernández (Cieza, 1987), María Cuartero (Murcia, 1984) and Santiago Cuevas (Cuenca, 1976) are successful cases in retrieving research talents who have fled society.

Cuevas, a researcher at the Murcian Institute for Biosanitary Research (IMIB-Arrixaca), has been working on implementing treatments to prevent diabetic nephropathy, the most common cause of kidney failure in the world, and left the region in 2009. , the crisis clouded a future that was already bleak due to lack of investment in science. There he was able to develop his work for ten years at prestigious research centers such as the Children’s National Medical Center or the George Washington and Maryland Universities. He also knows the private company where he worked before returning to Murcia. That is why, at the gates of the day of the regional elections, it is clear what are the main points that the next regional government should focus on in its efforts to improve the situation of science: «First, routine. A lot of money has to be invested. Efforts have been made and improvements are being made, and they are appreciated, but what we really need is funding for researchers. It’s not like they’re paying us, it’s not. A politician can assess what are the problems in the society, make plans to solve them and implement what the society demands from us.

-

Greater investment in science projects

Researchers are calling for more funding for research centers and projects focused on solving problems, as well as a regional strategy in the short and long term. -

Attract talent

Strengthen talent attraction and retention programs and facilitate the influx of top researchers. -

Stability

Budget continuity for projects and protection for professionals. -

Fewer distractions

Scientists lament having to spend a large percentage of their time on non-research tasks.

More stability is what Cuevas is asking from the region’s future government to bring back escaped talent. “The Spanish system, in the ten years that I have been away, has improved a lot. Although the basic problem is that scientific life is very complicated, in essence, it should be recognized. He believed in the Seneca Foundation’s ‘Saavedra Fajardo’ program by awarding a grant of 41,000 euros per year for three consecutive years. “I was in Washington. I got a call when I was there and they encouraged me to listen to it,” he says. “I am deeply grateful to them.” For this reason, it “encourages more mechanisms so that more experts from outside can reach our system. as? By passing laws that put pressure on the university to hire the best, sometimes that’s an innate environment. This will have a positive effect on the quality of work and teaching.

In the case of María Cuadero, who leads global research on chemical sensors at UCAM, the return is due to the university’s commitment to co-lead the UCAM-SENS chemical sensor research unit with Gaston Crespo. He has been there since last November. “UCAM strongly bet on my return to the region. Although the conditions of this attraction and the dedication and commitment to the program are very unusual and unusual in the region,” he admits.

María has received various awards from the International Society of Electrochemistry and Scientific Journals (Investigator and Chemical Sensors), she is a member of the Young Academy of Spain, President of Section 1 of the International Society of Electrochemistry and editor of the journal ‘Analysis’. Chemistry’. Like other Spanish researchers, after receiving his doctorate, he had to leave Spain, in his case, for Switzerland and Sweden, first as a researcher and then as a professor. There he was able to appreciate the great differences in the treatment of science with respect to Spain. “Switzerland and Sweden value science and researchers very much. In fact, Sweden is the European country that devotes the highest percentage of GDP to research, development and innovation. Then, almost two-thirds of investment in Switzerland is made to promote public-private partnerships,” he says. For this reason, one of its key claims for the future government is that it “encourages public-private collaboration, encourages excellence in research careers, and implements strategic research areas that have an impact on society.” In the same way, “more funding for research centers” and a regional investment strategy aimed at the short and long term should be allocated.

Fabio Julia Hernandez, from Chiesa, has been in the region for a short time since his return. His is the story of another long international trip that ended last January.

Emotional factor

The chemist began his career at the University of Murcia, where he completed his master’s and doctoral studies, worked in the pharmaceutical industry, moved to Manchester as a postdoctoral researcher, and studied at the Max Planck Institute in Germany. Last year he was recognized as an outstanding young researcher by the Royal Society of Chemistry. His research focuses on using light to trigger chemical reactions that allow him to develop new ways to access drugs more economically. And he spent a good part of these years searching for light. “The Spanish system survives through decisions of a personal nature, by researchers who want to return to the land, by the spirit of home, family, culture. That’s what happened in my case,” he explains. “Being able to be in the most powerful centers in Europe and return to UMU, I decided to lower my professional aspirations. No one put table conditions more than any other platform. There were good words and a lot of interest, but it was a personal race.

Ciezano hopes the regional executive can emulate some of the successful efforts nearby. “I’m not fooled, I’m not going to compare ourselves to other countries, but I think we should look at what other autonomous communities are doing, like the Igria project in Catalonia and the Valencian Community of Geant.” These measures will focus on “implementing more competitive and attractive programs” and providing a more sustainable path to attract and retain talent.

Thanks to a five-year Ramón y Cajal contract, Fabio Julia now sees a future in the region. “If all goes well, I will finally be able to approach permanent or stable status at age 40 or 41,” says the researcher.

Santiago Cuevas, for his part, won the Miguel Servet contract from the Carlos III Health Institute, one of the mechanisms for research integration in Spain. “Carlos III pays you for five years, but the center that receives you has the commitment to stabilize. Now, at almost 47, I can say that I have achieved stability.

Bureaucracy is a hindrance to work and return home

“The problem we have to escape from skills again is that those who work in England, America and other countries, who have been disconnected from our system for a long time, it is difficult to process the Anega authorization, because they have not done it. They do not know our procedures, and they find themselves with infinite bureaucracy to get jobs,” says Santiago Cuevas. . “Establish simple staffing criteria, promote them internationally, and make it easier for people from integrated environments abroad to come here,” the researcher asks. This is not just a dilemma arising from bureaucracy. Fabio Julia Hernandez points to the huge administrative burden as one of the issues that needs to be addressed. “Most research in Spain is done in public universities, where you are employed as a professor, so most of your time is devoted to administrative and teaching loads. That takes a lot of time. In other countries, they do everything possible so that scientists with a good track record can be fully committed. Far from the university At a distance, Cuevas acknowledges the efficiency loss caused by paperwork. “I spend 40% of my time on reports. And that’s not productive. I’m productive when I’m in the lab,” he laments. The slowness of management does not help: “I spent four months processing a document to work with animals. When I spoke to someone to deal with it, they said that I did not fill out a paper correctly.